Howard Hughes, a name synonymous with both aviation innovation and eccentric behavior, christened his ambitious project the H-4 Hercules. For the world, however, it became famously, and to Hughes’s chagrin, known as the “Spruce Goose.” This colossal aircraft, the largest and most powerful of its time, is remembered as much for its single, brief flight as for the enigma of its creator. Seventy-five years after its maiden voyage, we delve into the question: Why Did The Spruce Goose Only Fly Once?

The genesis of the Spruce Goose lies in the dire circumstances of World War II. By the early 1940s, German U-boats were wreaking havoc on Allied shipping in the Atlantic, severely disrupting the supply lines to Britain. The U.S. War Production Board urgently sought alternative methods for transporting troops and war materials. Henry J. Kaiser, a shipbuilding magnate renowned for his mass-production techniques, proposed an audacious solution: a fleet of massive flying cargo ships capable of soaring above the U-boat threat. To realize this vision, Kaiser needed an aviation expert, and he turned to Howard Hughes. Hughes, already a celebrated aviator and filmmaker known for his daring ventures, embraced the challenge. Building a 200-ton flying boat seemed like just another hurdle for a man who thrived on defying expectations.

Henry J. Kaiser, shipbuilder, with a model of the H-4 Hercules, highlighting the ambitious scale of the project.

Henry J. Kaiser, shipbuilder, with a model of the H-4 Hercules, highlighting the ambitious scale of the project.

Howard Robard Hughes Jr.’s background was as unconventional as the Spruce Goose itself. Born into wealth from his father’s innovative oil drill bit, Hughes quickly gravitated towards Hollywood and aviation. His 1930 aviation epic Hell’s Angels showcased his ambition and willingness to push boundaries, setting the stage for his future endeavors in flight. Hughes established the Hughes Aircraft Company in 1932, driven by a passion for air racing and pushing the limits of aviation technology. He shattered speed records, circumnavigated the globe in record time, and garnered accolades, including a Congressional Gold Medal for his contributions to aviation. This blend of financial resources and aviation expertise made him the ideal, albeit unconventional, partner for Kaiser’s ambitious flying boat project.

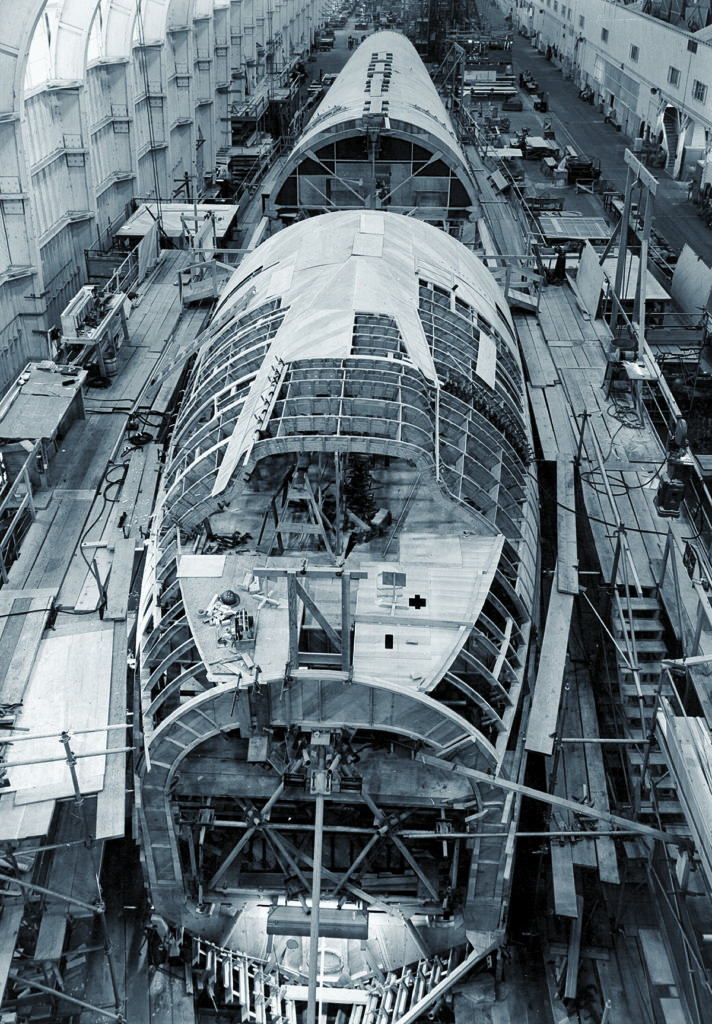

The H-4 Hercules under construction, dwarfing the workers and highlighting the immense scale of the aircraft.

The H-4 Hercules under construction, dwarfing the workers and highlighting the immense scale of the aircraft.

The partnership between Kaiser and Hughes, however, was an unlikely pairing. Kaiser, a pragmatic and publicly-minded industrialist, contrasted sharply with the reclusive and flamboyant Hughes. Despite their differences, they secured an $18 million government contract to develop three flying boat prototypes. The project was fraught with constraints: limited use of strategic materials like aluminum and steel, restrictions on hiring personnel already engaged in war efforts, and a tight 24-month deadline. Kaiser optimistically predicted completion within a year. In the fall of 1942, the unlikely duo embarked on their ambitious undertaking.

Engineers inspecting the massive Pratt & Whitney engines of the H-4 Hercules, emphasizing the power and complexity of the aircraft.

Engineers inspecting the massive Pratt & Whitney engines of the H-4 Hercules, emphasizing the power and complexity of the aircraft.

Hughes envisioned the HK-1, later known as the H-4, as a behemoth capable of carrying 750 troops or two Sherman tanks. Progress was slow and plagued by Hughes’s perfectionism and erratic behavior. His involvement in other projects, including the controversial film The Outlaw, and his two near-fatal aviation accidents in the 1940s further hampered development. By 1944, Kaiser, frustrated by the delays and Hughes’s management style, withdrew from the partnership. Hughes, undeterred, continued the project, pouring his own resources into what was now solely his endeavor.

Howard Hughes inside the H-4 Hercules, showcasing the cavernous interior intended for cargo and troops.

Howard Hughes inside the H-4 Hercules, showcasing the cavernous interior intended for cargo and troops.

The H-4’s construction was a feat of engineering ingenuity. Built primarily from Duramold, a plywood-like material made of birch, it circumvented wartime restrictions on metal. Despite its “Spruce Goose” moniker, the aircraft was largely birch. The sheer scale of the plane necessitated innovative manufacturing techniques, including projecting blueprints onto the factory floor for full-scale part construction. Hughes also pioneered hydraulic controls for the aircraft’s massive control surfaces. The wingspan, a record-breaking 320 feet, and eight powerful Pratt & Whitney engines were designed for long-range heavy cargo transport. However, by the time the H-4 neared completion in 1947, the war was over, and the original need for the aircraft had vanished. Accusations of mismanagement and misuse of government funds began to surface in Washington.

In August 1947, Hughes faced intense scrutiny from the Senate War Investigating Committee. Senator Owen Brewster famously dismissed the H-4 as a “flying lumberyard” that would never fly. Hughes, known for his defiance, passionately defended his project and his reputation. He famously declared, “I have stated that if it was a failure, I probably will leave this country and never come back, and I mean it.” Hughes turned the hearings into a public spectacle, even counter-attacking Senator Brewster with accusations of corruption. The public perception shifted in Hughes’s favor, and he returned to California determined to prove his critics wrong.

Howard Hughes piloting the H-4 Hercules on its only flight, demonstrating its ability to briefly take to the air.

Howard Hughes piloting the H-4 Hercules on its only flight, demonstrating its ability to briefly take to the air.

On November 2, 1947, before a crowd of onlookers and press, Hughes took the controls of the H-4 Hercules in Long Beach Harbor. After initial taxiing runs, in the third attempt, Hughes surprised everyone. He ordered flaps lowered, throttled the engines, and the massive flying boat lifted gracefully out of the water, soaring for 26 seconds at an altitude of 70 feet before a smooth touchdown. Radio reporter James McNamara, capturing the moment live, exclaimed, “Howard, did you expect that?” Hughes’s laconic reply: “I like to make surprises.”

So, why did the Spruce Goose only fly once? Several factors contributed to its singular flight:

- Changing War Needs: The H-4 was conceived during WWII for wartime transport. By 1947, the war was over, and the urgency for such a massive transport aircraft had diminished significantly. The government’s initial need and funding rationale evaporated with the end of the war.

- Hughes’s Focus on Proof of Concept: Hughes himself stated that the flight was for “testing and research and to provide knowledge.” His primary goal with the single flight was to demonstrate that the H-4 could fly, silencing his critics and vindicating his ambitious project. He achieved this objective with the brief but successful flight.

- Technological Limitations and Practicality: While a marvel of engineering, the Spruce Goose was arguably ahead of its time and potentially impractical for regular operation. Its wooden construction, while innovative, might have presented long-term durability and maintenance challenges compared to metal aircraft. The sheer size and operational costs would have also been significant hurdles.

- Hughes’s Shifting Interests: After proving the H-4 could fly, Hughes, ever the restless innovator, may have shifted his focus to other ventures. His interests were diverse, spanning aviation, filmmaking, and later, other industries. Maintaining and further developing the H-4 might not have aligned with his evolving priorities.

- Cost and Lack of Further Government Funding: The project was incredibly expensive, consuming substantial government funds and Hughes’s personal wealth. With the war over and no further government contracts on the horizon, the financial incentive to continue development and testing was likely absent.

The Spruce Goose at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum, its final resting place and a testament to aviation history.

The Spruce Goose at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum, its final resting place and a testament to aviation history.

Despite its single flight, the Spruce Goose remains an iconic symbol of American ingenuity and Howard Hughes’s audacious spirit. It stands as a testament to a time of wartime necessity, pushing the boundaries of aviation technology. Today, preserved at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum in Oregon, the H-4 Hercules continues to captivate visitors, reminding us of a unique chapter in aviation history and the audacious ambition behind the plane that flew only once.