It was the kind of day pulled straight from a coloring book: an expansive blue canvas dotted with fluffy white clouds, the yellow sun spotlighting nature’s vibrant greens, reds, and browns. Reb, my Philippine Cockatoo companion, perched atop a tree, proclaiming his mastery over all he surveyed. Then, in a moment of avian exuberance, he launched himself from his high branch, wings unfurling, and executed a flawless swoop of controlled flight. A true showman, always ready to dazzle!

Which Parrots are Primed for Free Flight?

In my previous article, we explored the essential qualities of the caretaker/trainer that are non-negotiable before even contemplating outdoor free flight. It’s crucial to remember that free flight is inherently risky and simply isn’t suitable for every caretaker or every parrot. Now, in Part Two, we’ll turn our attention to the parrot itself and examine the characteristics that make a bird a viable candidate for this incredible experience.

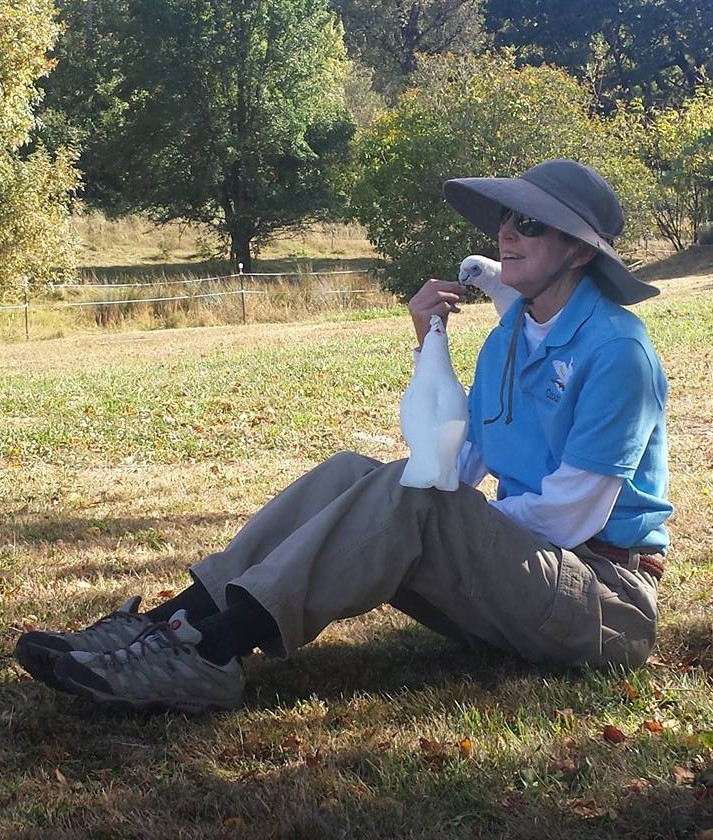

DSC_1905

DSC_1905

Reb embodies the ideal free flight parrot. Like all cockatoos, he was born with the innate tools for flight: pristine feather condition, fully formed wings and tail, sharp eyesight, strong legs and feet, and keen hearing – the complete package. He was, in essence, a standard wild cockatoo model, perfectly designed for navigating the forests of his native Philippines without needing any enhancements.

However, Reb’s destiny was not to be a wild cockatoo. He was destined to be my free-flying companion. His life would unfold not in the Philippine jungles, but within the more confined and artificial settings of cages, aviaries, and homes, punctuated by daily flights in the open air. His flight education had to be carefully sculpted to fit this unique lifestyle.

The Foundational Need for Fledging

Creating a top-tier companion parrot for free flight begins with an undeniable prerequisite: the parrot must be a skilled flyer. Equally important, the caretaker must understand what true flight proficiency looks like. Many parrot owners boast about their indoor birds being excellent flyers. Yet, a more seasoned observer often sees a different reality – a parrot still in the elementary stages of flight development. These birds might fly with weakness or hesitation, their in-flight decisions appear tentative, and landings are often clumsy.

Blue Bird

Blue Bird

Take a moment to watch local wild birds. They offer a masterclass in what a companion free flight parrot should aspire to. You’ll witness birds in complete command of their aerial movements. Notice their rapid, coordinated, and powerful take-offs and landings. There’s no uncertainty in their actions or reactions mid-flight. They navigate wind and rain with ease, as naturally as we walk. This is the level of flight mastery we aim for in our free-flying companions.

Fledging represents the optimal and biologically timed period for any bird to master flight. It’s a critical window of intense learning for young parrots. Once this developmental window closes, achieving flight mastery becomes significantly more challenging.

If a parrot destined for free flight doesn’t develop proficient flight skills during fledging, the consequences can be severe. It’s akin to putting a sixteen-year-old with minimal driving experience behind the wheel in rush hour traffic – a scenario fraught with potential mishaps.

The Fledging Process: Nature’s Flight School

A young parrot doesn’t emerge from its nest a fully formed aerial ace. Flight skills develop gradually, beginning in the nest itself. Here, the fledgling parrot engages in wing-flapping exercises, building essential muscle strength even before feathers fully develop. As it ventures out of the nest, coordination and strength increase through practice and exploration. Providing a spacious outdoor aviary during fledging offers the young parrot the perfect environment to cultivate muscles, refine coordination, and build aerial confidence.

Perching in Aviary

Perching in Aviary

Years ago, my parent-raised Bare-eyed Cockatoos provided their fledglings with an exceptional flight education. As the young birds left their nest box, they remained close to their parents within the aviary. After a few days of aviary-based flight practice, I released the family into the open outdoors, where the parents flew to a nearby ash tree.

The fledglings followed, and under the watchful eyes of their parents, spent the day climbing in the tree, practicing short flights from branch to branch. The parents actively encouraged exercise, moving around the tree and flying back to the aviary. The youngsters mirrored their behavior, steadily growing stronger and more confident with each flight. In less than a week of this routine, the fledglings’ flight skills improved dramatically, showcasing the effectiveness of natural, parent-guided fledging.

Does Parrot Species Matter for Flight?

Recently, I encountered an online query from someone considering free flight: “Which species is better suited for free flight, a Galah or an African Grey?” One response suggested a Galah was superior because the Grey was “wide-bodied.” This notion is simply unfounded! The idea that being “wide-bodied” hinders a Grey’s flight ability is easily debunked by observing wild flocks of African Greys in flight. Their aerial maneuvers are a display of precision and agility; their body shape certainly doesn’t seem to hold them back.

imagesCAG0IJ72

imagesCAG0IJ72

My point is that all bird species that have evolved to fly well, do so effectively. Species with less refined flight capabilities, like domestic turkeys, chickens, or quail, have developed alternative survival strategies to compensate for their flight limitations. Flight proficiency is more about individual development and opportunity than inherent species limitations within parrots.

The Significance of Parrot Size in Free Flight

Size does play a role when selecting a free flight candidate, particularly concerning predator threats. Larger parrot species, such as macaws and large cockatoos, are generally less vulnerable to attacks from smaller raptors like Cooper’s hawks. Cooper’s hawks, common in the United States, typically hunt smaller birds. They are less likely to target a large macaw or cockatoo but would readily prey on a conure or Senegal. However, it’s crucial to remember that any parrot, regardless of size, can be a target for a hungry bird of prey.

Cooper

Cooper

I regularly fly smaller cockatoos like Goffin’s, Bare-eyeds, and Philippine Cockatoos. Their smaller size makes me acutely aware of the potential risk of Cooper’s hawk attacks.

And such attacks have occurred. There is safety in numbers, however. My parrots always fly in groups of at least three or more. More eyes on the sky mean better chances of spotting danger.

Even with impeccable training, flying a parrot alone significantly increases the risk. Group flights enhance safety through collective vigilance.

The Parrot’s Age and Free Flight Training

The age of a parrot is a crucial factor influencing the success of free flight training. Most experienced trainers prefer to work with younger parrots, ideally under one year old, for outdoor free flight training.

Many people wish to free fly older companion parrots, those well past their first year. Training older parrots for free flight can be considerably riskier, demanding careful consideration of various factors.

bird-1298346__340

bird-1298346__340

One critical aspect is the older parrot’s learning history and life experiences. Consider: Has the parrot been trained using positive reinforcement? Is it an enthusiastic learner? Does it have a solid foundation in flight? Has it had ample opportunity for flight in an aviary or only indoors? Does it primarily use flight for movement? Does it fly confidently and without hesitation? Is it fearful of new experiences or adaptable?

Another vital consideration is the older parrot’s health. Is it robust and healthy? Are there any physical disabilities? Does it have good eyesight? Are its feathers in excellent condition? A thorough and honest evaluation of these factors is essential to determine if an older companion parrot is suitable for free flight training.

While it’s more challenging, older parrots can learn to free fly. My Goffin’s Cockatoo, Topper, joined my family in his early twenties. He had a history of indoor flight and was remarkably skilled at navigating my home.

Topper in flight

Topper in flight

His confidence, skill, and strength convinced me he might be a candidate for free flight. I started his training, and he excelled, earning his wings outdoors. His success was due to his spirited and curious nature, excellent health, pre-existing flight skills, and eagerness to learn.

However, Topper’s story is the exception, not the rule. Most older parrots are not suitable for free flight. If you’re considering free flight for your older parrot, seeking evaluation from an experienced mentor is the most prudent first step.

Essential Elements for Free Flight Success

This article is intended to illuminate the rigorous requirements for selecting a suitable parrot for free flight, not as a comprehensive training manual.

Crucially, I must reiterate the vital role of a skilled companion free flight trainer. Caretakers must possess and apply effective training techniques while working with a knowledgeable in-person mentor to guide the free flight development process. Without these two fundamental components, no parrot, young or old, should be considered a free flight candidate.

Witnessing your parrot soar through the open sky, skillfully maneuvering through the wind or landing atop the highest tree, is an unparalleled joy. It’s a dream for many parrot enthusiasts. However, I implore you to take the considerations discussed in this article and my previous commentary (Part One) on free flight with utmost seriousness.

Despite its allure, free flight is not for casual parrot owners or untrained birds. It’s an extreme sport that offers immense highs but also carries the potential for profound heartbreak. If you are contemplating this path, please proceed with extreme caution and seek expert guidance.

The Latest Chick News!

38 days old

38 days old

Our baby Bare-eyed Cockatoo (BBE) is thriving and growing into a miniature version of her species. Her pin-cushion body is now covered in smooth white feathers, she can raise her crest, and her eye patches are developing a lovely gunmetal grey. Her parents are doing a fantastic job nurturing her. As of this writing, she is forty-four days old, and we anticipate fledging in another 4 to 5 weeks. Exciting times are ahead!

Just for Fun with Ellie!

Ellie

Ellie

Meet Ellie! Miss Ellie joined us at Cockatoo Downs almost two weeks ago. I adopted her from a wonderful local rescue organization, Exotic Bird Rescue, in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. They have an excellent network of foster homes for relinquished parrots.

After losing my beloved Asta Bare-eyed to cancer, I decided to welcome another Bare-eyed Cockatoo into my life. Asta was a free flyer who lived in the aviary with her flock. During her illness, she lived indoors with me, reminding me how much joy I had been missing by not having a “house” bird. After she passed, the house felt empty, prompting my search for a Bare-eyed Cockatoo in Asta’s memory.

It’s been a delightful adventure getting to know Ellie. We are both learning about each other. After just a week, she seems to have decided I’m an acceptable roommate, and I know I made the right choice in bringing her into our family.

Ellie is a confident little bird, not easily intimidated. She’s exploring her new home and increasingly flying around on her own, using ropes and a large orbit I hung for her. She’s already learned to target a chopstick and politely steps up, often lifting her foot to signal she’s ready.

Ellie in Aviary(2)

Ellie in Aviary(2)

I built an aviary on the front deck, connected to the front window, giving her easy access. It measures 10 feet long, 7 feet high, and 5 feet wide. I used electrical conduit pipe from Home Depot, canopy attachments from canopy supply websites for the corners, and 1/2 by 1/2-inch galvanized wire from another home improvement store. This setup is ideal for daytime use. The cost was around $150, and it took me about five days, working a couple of hours each day, to assemble it.

Ellie in Aviary

Ellie in Aviary

Today, I showed her the open window to the aviary for the first time. She cautiously ventured onto the aviary perch, thoroughly inspected her new space, deemed it satisfactory, and even started “decorating” by chewing on a perch!

Even though Ellie arrived in good health and feather condition, I expect both to improve with the sunshine and fresh air the aviary provides. My homemade aviary is simple, not fancy, but it provides all the fresh air and sunshine a parrot needs to thrive. Consider building one for your companion parrots – they will thank you for it!

For aviary design inspiration, check out the Facebook page “Home Aviary Design.” It’s a closed group, but membership is open to anyone interested.

Chris Shank’s passion for parrots and expertise in animal training spans decades. Her credentials include a degree from the Exotic Animal Training and Management Program at Moorpark College, an internship at Busch Gardens’ parrot show, and experience as a dolphin trainer at Marriott’s Great America and in Germany.

Chris Shank, an internationally recognized expert in free flight, with extensive experience in parrot training and care.

Chris Shank, an internationally recognized expert in free flight, with extensive experience in parrot training and care.

Her fascination with cockatoos began during a relocation to the Philippines. Upon returning to the United States, she established Cockatoo Downs, offering training and education to parrot owners for many years. She is a globally recognized authority on free flight.