Birds embarking on their southward journey, often seen in classic V-formations of geese against the autumn sky, is a quintessential image of migration. This incredible annual movement, involving birds traveling between their breeding grounds and wintering areas, is not limited to geese. In fact, over half of the 650+ breeding bird species in North America are migratory. But When Do The Birds Fly South, and what triggers this remarkable journey?

Brown-gray birds with black and white head, neck and tail feathers, long necks outstretched, flying.

Brown-gray birds with black and white head, neck and tail feathers, long necks outstretched, flying.

Canada Geese in Flight. Alt text: A flock of Canada Geese soars in a V-formation against a bright sky, showcasing their southward migration.

The Driving Force Behind Bird Migration: It’s All About Food

While escaping the cold might seem like an obvious reason for birds to fly south, the primary driver is food availability. As Dr. Kevin McGowan from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology explains, migration is “almost always about finding food.” Many birds rely on insects and plants that become scarce during colder months in northern regions. While some birds, like chickadees in boreal forests, can find enough food to survive winter, insect-eating birds must seek out areas where food remains plentiful.

Daylight Changes: The Signal to Migrate South

So, when do birds know to fly south? The key trigger isn’t temperature, but changes in daylight length. As days shorten in late summer and fall, birds sense these subtle shifts, initiating a physiological response. This change in daylight affects their hormones, prompting what’s known as Zugunruhe, or migratory restlessness. This restlessness is a compelling urge to move, to travel south in search of better conditions. Even captive birds exhibit this behavior, becoming agitated as daylight hours decrease, showcasing the innate drive to migrate.

Migration Timing: A Mix of Precision and Flexibility

While the urge to migrate south is linked to daylight changes, the exact time when birds fly south can vary. For some species, migration timing is remarkably precise. Red-winged Blackbirds, for example, consistently arrive in central New York within a two-week window each year. However, migration isn’t rigidly fixed. Individual bird behavior is also influenced by weather patterns and local conditions. Factors like food availability along the route or unexpected storms can cause birds to adjust their departure or arrival times, demonstrating a blend of instinct and adaptability in their migration schedule.

Who Flies First? Age and Sex Dynamics in Southward Migration

Interestingly, not all birds migrate south at the same time or in the same groups. There’s a distinct pattern based on sex and age. Typically, breeding males of many species begin their southward migration first, ahead of females and juvenile birds. Adult birds generally precede juveniles in the migration journey. This staggered migration could be due to various factors, perhaps adult birds are better prepared for the journey, or juveniles need more time to build up fat reserves before undertaking the demanding flight south.

Night Flights: A Common Strategy for Migrating South

Many people are surprised to learn that the majority of bird migration occurs at night. There are several advantages to nocturnal migration. Firstly, flying at night reduces the risk of predation, as fewer daytime predators are active. Secondly, nighttime often offers calmer air and favorable wind conditions. Furthermore, migrating at night allows birds to conserve energy by foraging during the day and flying when it’s cooler. Perhaps most fascinatingly, some research suggests that nighttime flights enable birds to utilize their magnetic sense to navigate using the Earth’s magnetic fields, especially when visual cues are limited in darkness.

Yellow Warbler Navigating with Magnetic Fields. Alt text: Illustration depicting a Yellow Warbler using Earth’s magnetic field lines for navigation during its nighttime southward migration.

Helping Birds on Their Southward Journey

As birds undertake their long and arduous journey south, we can take actions to help them along the way. For hummingbirds, keeping hummingbird feeders filled provides a valuable energy source for their migration. For other species, offering suet can be beneficial. One of the most impactful things we can do, particularly in urban areas, is to reduce light pollution. Turning off unnecessary lights at night during peak migration periods can significantly reduce bird collisions with buildings. Initiatives like BirdCast’s Lights Out program are crucial in raising awareness about this issue and encouraging cities to dim their lights for migrating birds. Planting native plants in our gardens also provides natural food sources and habitats for migrating birds, offering vital support during their travels.

Types of Bird Migration: Short Hops to Epic Journeys South

Bird migration isn’t a monolithic phenomenon. It encompasses a range of movements, classified by distance.

- Permanent Residents: Some birds, like the Northern Cardinal, don’t migrate at all. They remain in the same area year-round, finding sufficient food resources throughout the seasons.

northern cardinal

northern cardinal

Northern Cardinal: A Permanent Resident. Alt text: A vibrant male Northern Cardinal perched on a snowy branch, illustrating birds that do not migrate south.

- Short-Distance Migrants: These birds make relatively small movements, often altitudinal migration, moving from higher elevations to lower ground during colder months, like the Northern Bobwhite.

northern bobwhite

northern bobwhite

Northern Bobwhite: A Short-Distance Migrant. Alt text: A Northern Bobwhite standing amidst dry grasses, representing birds that migrate short distances.

- Medium-Distance Migrants: Birds in this category, such as Blue Jays, travel distances spanning a few hundred miles, often within the same country or region.

blue jay

blue jay

Blue Jay: A Medium-Distance Migrant. Alt text: A Blue Jay perched on a branch, symbolizing birds that undertake medium-distance migrations.

- Long-Distance Migrants: These are the champions of migration, undertaking incredible journeys from breeding grounds in the US and Canada to wintering areas in Central and South America. The Magnolia Warbler is a prime example.

Magnolia Warbler by Gerrit Vyn

Magnolia Warbler by Gerrit Vyn

Magnolia Warbler: A Long-Distance Migrant. Alt text: A Magnolia Warbler perched on a branch with green leaves, exemplifying birds that migrate vast distances south.

Unraveling the Origins of Long-Distance Southward Migration

The origins of long-distance migration, particularly southward migration to the tropics, are complex and fascinating. One prominent theory suggests that the ancestors of many North American migratory birds originated in the tropics. Over generations, these tropical birds expanded their breeding ranges northward, taking advantage of abundant summer food and longer daylight hours for raising more offspring. As seasons changed and winter approached, the instinct to return to the ancestral tropical wintering grounds remained ingrained, leading to the evolution of long-distance southward migration patterns we observe today. This theory is supported by the fact that many North American migratory bird families, like vireos, warblers, and orioles, have evolutionary roots in the tropics.

BirdCast: Predicting When Migration Intensity Peaks

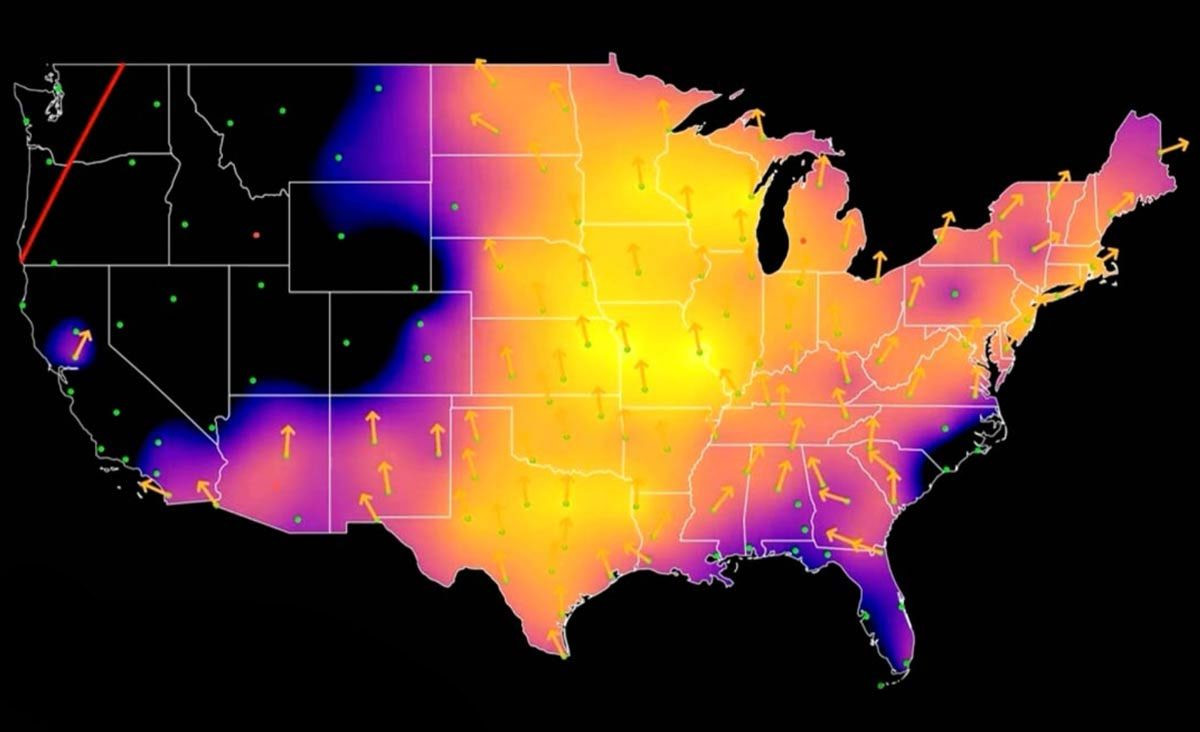

To better understand when birds fly south on a larger scale, tools like BirdCast are invaluable. Using weather radar, BirdCast provides real-time maps of nocturnal bird migration intensity across the continent. It even offers 3-day migration forecasts, predicting nights of heavy migration activity. This information is crucial for conservation efforts, aiding decisions about wind turbine placement and informing city initiatives like Lights Out programs to minimize hazards for migrating birds. BirdCast helps us visualize the massive scale of bird migration and anticipate when birds will be flying south in large numbers in different regions.

map of the continental U.S. showing intensity of bird migration, 2021

map of the continental U.S. showing intensity of bird migration, 2021

BirdCast Migration Intensity Map. Alt text: A BirdCast map of the continental US showing varying intensities of bird migration, useful for predicting when birds fly south.

Navigation Marvels: How Birds Find Their Way South

The navigational abilities of migrating birds are truly astonishing. Many birds travel thousands of miles, often following the same routes year after year, with young birds undertaking their first migration solo. How do they manage this feat? Birds employ a combination of navigational tools. They use the sun, stars, and Earth’s magnetic field as compass cues. Landmarks, the position of the setting sun, and even their sense of smell may also play a role. Waterfowl and cranes often utilize established flyways, following routes with critical stopover locations for refueling. Smaller birds tend to migrate across broader fronts, sometimes even taking different routes in spring and fall to optimize for weather and food availability.

Hazards of the Southward Journey

The journey south is fraught with dangers. Migrating birds face immense physical exertion, food scarcity along the way, unpredictable weather, and increased predator exposure. In recent times, human-made structures pose a significant threat, particularly tall buildings and communication towers. Attracted by artificial lights, millions of birds are killed annually in collisions. Organizations like the Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP) and BirdCast’s Lights Out project are working to mitigate this threat by promoting light reduction strategies during migration periods.

Migrant Traps: Havens During Southward Migration

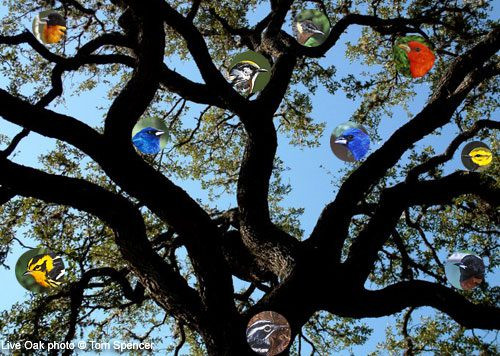

Certain locations become magnets for migrating birds, known as “migrant traps.” These hotspots often arise due to weather patterns, abundant food sources, or topographical features. For example, coastal areas along the Gulf of Mexico become critical landing points for songbirds migrating north across the Gulf. When headwinds or storms strike, exhausted birds seek refuge in the nearest land offering food and shelter, often live-oak groves. Peninsulas, like Cape May and Point Pelee, also act as migrant traps, concentrating birds before they embark on overwater flights. These migrant traps provide crucial stopover habitats for birds on their southward journey, and are popular birdwatching destinations.

Illustration of a tree with images of different birds.

Illustration of a tree with images of different birds.

Migrant Trap Habitat. Alt text: Illustration of a live oak tree teeming with various songbirds, typical of migrant trap habitats where birds gather during migration.

Range Maps: Predicting Bird Presence Throughout the Year

Field guides with range maps are valuable tools for understanding when birds might be flying south or be present in a particular area. Range maps illustrate the typical distribution of species throughout the year, particularly helpful for migratory birds. However, traditional range maps have limitations, as bird ranges can shift due to factors like climate change or irruptions. Digital, data-driven range maps, powered by vast datasets like eBird observations, offer a more dynamic and current view of bird distributions. These animated maps reveal the seasonal ebb and flow of bird populations across continents, providing a more nuanced understanding of when and where birds migrate south.

Conclusion: Appreciating the Wonder of Southward Bird Migration

Understanding when birds fly south reveals the intricate relationship between birds and their environment. Migration is a complex, awe-inspiring phenomenon driven by food availability, triggered by changing daylight, and navigated with remarkable skill. By learning about bird migration, we can better appreciate the challenges these birds face and take steps to support them during their incredible journeys. Resources like BirdCast and initiatives promoting light reduction are vital in ensuring safe passage for millions of birds as they embark on their annual flights south.

Additional Resources

To delve deeper into the fascinating world of bird migration, consider exploring these resources:

- Songbird Journeys by Miyoko Chu

- Handbook of Bird Biology from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- BirdCast: https://birdcast.info/

- Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP): http://flap.org/

American Kestrel. Alt text: An American Kestrel perched on a branch, representing the diverse species involved in southward bird migration.