Fruit flies, those tiny, persistent pests that seem to materialize out of thin air around your fruit bowl, are a common nuisance. A popular saying suggests you can catch more flies with honey than vinegar, but when it comes to Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly, vinegar plays a surprisingly significant role in their attraction to food sources. These flies, in their adult stage, are naturally drawn to fermenting fruit, relying heavily on their keen sense of smell to locate the acetic acid – the very compound that gives vinegar its characteristic pungent smell. This acetic acid is a key indicator of overripe fruit, a prime location for the microbes they feed on. However, it’s not a simple case of indiscriminate attraction; fruit flies typically exhibit a nuanced response to vinegar, often ignoring or even avoiding both very low and very high concentrations. Low concentrations might signal unripe fruit, while high concentrations could indicate spoilage beyond their preference.

But what happens when hunger strikes? Groundbreaking research has shed light on the fascinating changes that occur within a fruit fly’s brain when it’s hungry, altering its perception and broadening its acceptance of vinegar odors. A study led by Jing Wang and Kang Ko at the University of California, San Diego, published in eLife, elegantly details the neural mechanisms that enable hungry flies to be drawn to a wider spectrum of vinegar concentrations than their well-fed counterparts. Their findings reveal that starvation doesn’t just amplify a fly’s overall sensitivity to food odors. Instead, it triggers a sophisticated and selective modulation of their olfactory processing, initiating specific excitatory and inhibitory responses that compel them to seek out and forage on food sources that would normally be considered less than ideal. This research subtly reinforces the human experience – perhaps it’s indeed unwise to grocery shop on an empty stomach, as hunger might compromise our ability to distinguish between truly good food and less desirable options.

graphic file with name elife10535inf001.jpg

graphic file with name elife10535inf001.jpg

This work builds upon a foundation of previous research into how Drosophila process olfactory information, particularly concerning vinegar. Similar to humans and other vertebrates, fruit flies possess olfactory neurons specialized to detect specific airborne chemicals. These neurons connect to discrete clusters of synapses in the brain called glomeruli. Neurons detecting the same odorant converge on the same glomerulus. Vinegar odor, depending on its concentration, activates roughly 6 to 8 out of the approximately 40 glomeruli in a fruit fly’s brain. Notably, a landmark study from the Wang group previously highlighted the DM1 glomerulus as a primary driver of a fly’s attraction to vinegar. Disrupting the receptors associated with DM1 effectively made flies indifferent to vinegar. Conversely, selectively restoring DM1 neuron activity in flies with a severely impaired sense of smell was sufficient to reinstate their attraction to vinegar.

Higher vinegar concentrations engage an additional glomerulus, DM5. Intriguingly, DM5 activity alone can explain why flies tend to avoid vinegar when the odor becomes too strong. Therefore, the interplay between DM1 and DM5, activated at varying vinegar concentrations, appears to be a crucial determinant in a fruit fly’s decision to approach or avoid a potential food source.

The profound influence of hunger on animal behavior is well-documented. Hungry fruit flies, for instance, are significantly faster at locating a small amount of vinegar-laced food compared to flies that have recently fed. Insulin, a hormone, indirectly mediates this effect. Starvation leads to a decrease in insulin levels, initiating a cascade of events that ultimately boost the expression of a specific receptor protein in DM1 olfactory neurons. This receptor is sensitive to a signaling molecule called short neuropeptide F. When short neuropeptide F binds to this receptor, it effectively amplifies the activity of DM1. Given DM1’s role in vinegar attraction, this mechanism seemed to provide a clear explanation for how insulin signaling drives hungry flies to become more active in their search for food.

However, the latest research reveals a more complex picture. By testing a broader range of vinegar concentrations, Ko and colleagues discovered that the neuropeptide F mechanism primarily explains the increased attraction to low vinegar odor concentrations in hungry flies. Even when short neuropeptide F signaling is reduced, starved flies still exhibit a stronger attraction to vinegary food at higher concentrations compared to their fed counterparts. This suggested the involvement of another hunger signal. To identify this missing link, the researchers explored other receptor proteins that were upregulated in sensory neurons due to starvation. The Tachykinin receptor (DTKR) emerged as a compelling candidate, particularly because it was already known to have a role in dampening the responses of olfactory neurons in flies.

The subsequent findings unfolded logically: reducing DTKR levels indeed diminished food-finding behavior in hungry flies exposed to high vinegar odor concentrations, but not at low concentrations. Similarly, the activity of DM5, the glomerulus associated with avoidance of high vinegar levels, was lower in starved flies. However, when DTKR was suppressed, DM5 activity in starved flies returned to levels observed in well-fed flies. Finally, the researchers identified insulin as the likely upstream signal regulating DTKR in starved flies.

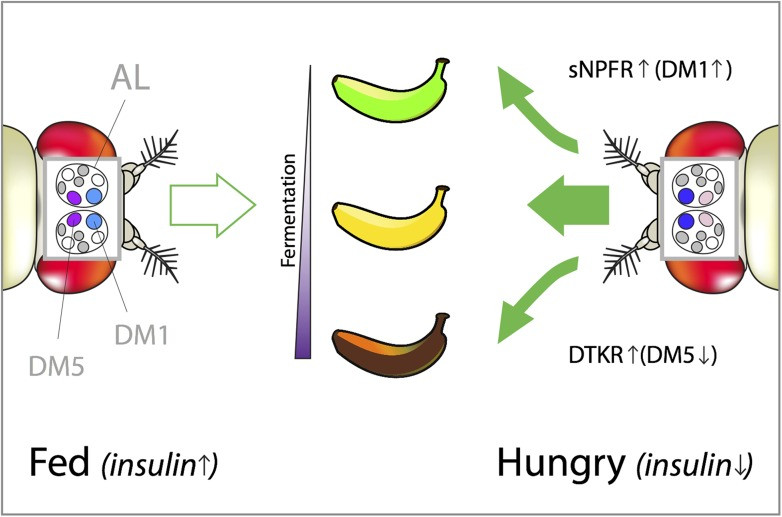

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

In conclusion, the evidence points to a model where declining insulin levels in starved flies activate two complementary neuropeptide signaling systems involving short neuropeptide F and Tachykinin. One system enhances signal transmission in the DM1 glomerulus, increasing sensitivity to appealing food odors. Simultaneously, the other system reduces transmission in DM5, making flies less averse to normally repellent or unpleasant smells. These combined effects enable fruit flies to pursue less-than-optimal food sources when food is scarce, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. How hunger influences the attractiveness of food odors in Drosophila.

Vinegar (acetic acid) is a byproduct of fruit fermentation, explaining fruit flies’ attraction to its scent. However, flies typically show indifference to both low and high vinegar concentrations (left). Low concentrations suggest unripe fruit (like a green banana), while high concentrations indicate over-ripe or rotten fruit (like a brown banana). Hungry flies, however, behave differently. Low insulin levels, a consequence of starvation, trigger two distinct neuropeptide signaling pathways that reshape their olfactory responses (right). In hungry flies, the receptor for short neuropeptide F (sNPFR) is upregulated in specific olfactory neurons. This enhances signal transmission within the DM1 glomerulus, increasing sensitivity to low concentrations of attractive food odors. Concurrently, elevated Tachykinin signaling (via the DTKR receptor) inhibits signal transmission within the DM5 glomerulus. This reduces avoidance of normally unpleasant smells, such as high vinegar concentrations. Together, these effects enable the pursuit of less-than-optimal food sources, indicated by the green arrows pointing towards both just-ripe and rotten bananas. DM1 and DM5 are specific glomeruli in the antennal lobe (AL) of the fly brain, and their color intensity reflects their activation strength in fed versus hungry flies.

This research underscores the fruit fly as a powerful model for studying how the brain processes sensory information. Utilizing elegant behavioral experiments, advanced genetic manipulations, and brain activity imaging, this study elucidates how a crucial sensory cue is processed differently based on an animal’s internal state – whether it’s hungry or satiated. Given the evolutionary conservation of many biological mechanisms, insights gained from fruit flies often hold relevance to other species, including humans. This area of research is poised to reveal fundamental principles of sensory processing that may be broadly applicable across the animal kingdom.

References

Ko KI, Root CM, Lindsay SA, Zaninovich OA, Shepherd AK, Wasserman SA, Kim SM, Wang JW. 2015. Starvation promotes concerted modulation of appetitive olfactory behavior via parallel neuromodulatory circuits. eLife 4:e08298. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08298

Semmelhack JL, Wang JW. 2009. Selectivity of olfactory neurons in Drosophila. Nature 459:218–23. doi: 10.1038/nature07984.

Root CM, Masuyama H, Green KN, Enell CS, Park JH, Wang JW. 2011. Glucosensing neurons mediate осмотической stress resistance in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:13543–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102839108.

Ignell R, Rohwedder A, Sachse S. 2009. Sensory and central processing of repellent odourants in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Biol Sci 276:2305–14. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0305.