Can I Fly Today? That’s the first question on every pilot’s mind, especially those learning to fly. At flyermedia.net, we provide the insights you need to make informed decisions about your flight, focusing on safety and regulatory compliance. We’ll delve into how to check weather conditions, interpret aviation weather reports, and understand the critical factors that affect your ability to fly safely, ensuring you stay up-to-date with aviation news, weather patterns, and temporary flight restrictions (TFRs).

1. The Importance of Pre-Flight Weather Checks

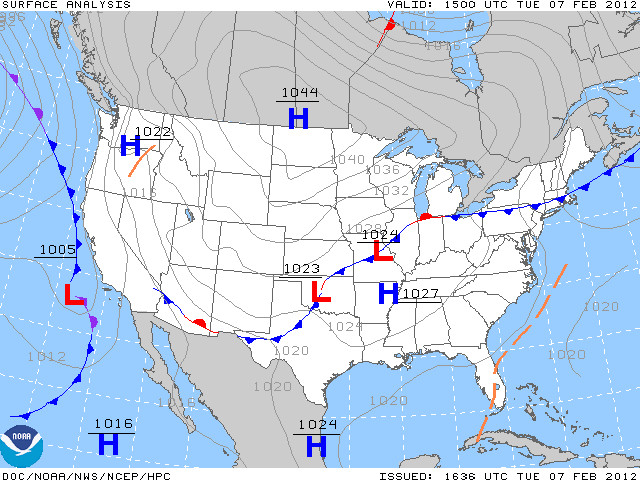

A successful and safe flight begins long before you step into the cockpit. A thorough pre-flight weather check is paramount, enabling pilots to make informed go/no-go decisions. This involves gathering and interpreting weather data to assess potential hazards and ensure the flight can be conducted safely. Understanding weather patterns and how they might affect your flight path is crucial.

1.1. Why Weather Checks are Essential for Pilots

Weather checks are not just a formality; they are a critical component of flight safety. According to the FAA, weather-related incidents are a significant cause of aviation accidents. A proper weather check helps pilots:

- Identify potential hazards such as thunderstorms, icing conditions, and turbulence.

- Plan the flight route to avoid adverse weather.

- Assess the impact of wind, visibility, and cloud cover on flight operations.

- Make informed decisions about whether to proceed with the flight.

1.2. Regulatory Requirements for Weather Briefings

Aviation regulations mandate that pilots obtain a weather briefing before any flight. The FAA requires pilots to be familiar with all available weather information pertinent to the intended flight. This includes:

- METARs (Meteorological Aviation Reports): Current weather conditions at airports.

- TAFs (Terminal Aerodrome Forecasts): Weather forecasts for specific airports.

- NOTAMs (Notices to Airmen): Information on temporary flight restrictions and other important notices.

- PIREPs (Pilot Reports): Reports from other pilots about actual weather conditions encountered in flight.

1.3. Real-World Consequences of Ignoring Weather Information

Ignoring or inadequately assessing weather information can lead to severe consequences. Accidents caused by adverse weather can result in injuries, fatalities, and significant damage to aircraft. Historical incidents underscore the importance of meticulous weather checks:

- Continental Airlines Flight 1404 (2008): A Boeing 737 crashed during takeoff in Denver due to strong crosswinds.

- Comair Flight 5191 (2006): A CRJ-200 crashed during takeoff in Lexington, Kentucky, due to fog and poor visibility.

- Delta Air Lines Flight 191 (1985): A Lockheed L-1011 crashed in Dallas, Texas, due to wind shear from a thunderstorm.

These examples highlight the potentially catastrophic outcomes of neglecting weather checks. Always prioritize a comprehensive weather assessment before every flight.

Importance of Pre-Flight Planning and Weather Checks

Importance of Pre-Flight Planning and Weather Checks

2. Essential Weather Resources for Pilots

To make sound decisions, pilots need access to a variety of reliable weather resources. These resources provide up-to-date information and forecasts, helping pilots assess the feasibility and safety of their flights. From official aviation weather websites to mobile apps, many tools are available to aid in pre-flight planning.

2.1. Aviation Weather Websites and Tools

Several websites offer comprehensive weather information tailored for pilots. These platforms provide real-time data, forecasts, and analysis tools to assist in flight planning. Key resources include:

- Aviation Weather Center (AWC): The AWC, part of the National Weather Service, offers METARs, TAFs, weather charts, and forecasts. According to the AWC, pilots should use these resources to understand current and predicted weather conditions along their route.

- Flight Service: Provides weather briefings, flight planning services, and NOTAM information. Pilots can call Flight Service for personalized weather briefings.

- National Weather Service (NWS): The NWS offers general weather information, including forecasts, radar images, and severe weather alerts.

2.2. Understanding METARs and TAFs

METARs and TAFs are essential tools for understanding current and future weather conditions. Decoding these reports accurately is crucial for safe flight operations.

- METARs: These reports provide current weather conditions at an airport, including wind speed and direction, visibility, cloud cover, temperature, and dew point.

- Example:

KEMT 071747Z 02005KT 13SM DZ BKN060 OVC080 A2994KEMT: Airport identifier (El Monte Airport).071747Z: Date and time (7th day of the month at 1747 Zulu time).02005KT: Wind from 020 degrees at 5 knots.13SM: Visibility of 13 statute miles.DZ: Drizzle.BKN060: Broken clouds at 6,000 feet above ground level (AGL).OVC080: Overcast clouds at 8,000 feet AGL.A2994: Altimeter setting of 29.94 inches of mercury.

- Example:

- TAFs: These forecasts predict weather conditions at an airport for a specified period, typically 24 to 30 hours.

- Example:

KBUR 071747Z 0718/0818 VRB06KT P6SM SCT050 OVC080KBUR: Airport identifier (Burbank Airport).071747Z: Date and time of issue (7th day of the month at 1747 Zulu time).0718/0818: Valid period (from 1800 Zulu time on the 7th to 1800 Zulu time on the 8th).VRB06KT: Variable wind direction at 6 knots.P6SM: Visibility greater than 6 statute miles.SCT050: Scattered clouds at 5,000 feet AGL.OVC080: Overcast clouds at 8,000 feet AGL.

- Example:

2.3. Mobile Apps for Real-Time Weather Updates

Mobile apps provide convenient access to weather information on the go. These apps often include features such as radar imagery, weather alerts, and flight planning tools. Popular aviation weather apps include:

- ForeFlight: A comprehensive flight planning app that includes weather briefings, charts, and navigation tools.

- Garmin Pilot: Offers weather information, flight planning, and electronic flight bag (EFB) capabilities.

- Avare: A free aviation app that provides weather information, charts, and GPS navigation.

2.4. Understanding PIREPs (Pilot Reports)

PIREPs are reports from pilots about actual weather conditions encountered in flight. These reports can provide valuable information about turbulence, icing, and other weather phenomena that may not be accurately reflected in METARs or TAFs. PIREPs are categorized into two types:

- Routine (UA): Reports of general weather conditions.

- Urgent (UUA): Reports of hazardous weather conditions, such as severe turbulence or icing.

- Example:

LGB UA /OV SLI315005/TM 1708/FL025/TP C152/WX -RA/TB LGT-MOD SMOLGB: Reporting station (Long Beach).UA: Routine pilot report.OV SLI315005: Over Seal Beach VORTAC, 315 degrees at 5 nautical miles.TM 1708: Time of report (1708 Zulu).FL025: Flight level 2,500 feet.TP C152: Aircraft type Cessna 152.WX -RA: Light rain.TB LGT-MOD SMO: Light to moderate turbulence, smooth.

- Example:

3. Key Weather Factors Affecting Flight Safety

Several weather factors can significantly impact flight safety. Understanding these factors and how they affect aircraft performance is crucial for pilots. Here, we look at visibility, ceiling, wind, icing, and turbulence.

3.1. Visibility: Importance and Minimum Requirements

Visibility refers to the horizontal distance at which prominent objects can be seen and identified. Poor visibility can make navigation difficult and increase the risk of collision. According to FAA regulations:

- VFR (Visual Flight Rules): Requires a minimum visibility of 3 statute miles for controlled airspace and 1 statute mile for uncontrolled airspace.

- IFR (Instrument Flight Rules): Allows flights in lower visibility conditions, but requires pilots to rely on instruments for navigation.

3.2. Ceiling: Defining Safe Cloud Clearance

The ceiling is the height above the ground of the lowest layer of clouds reported as broken or overcast. Low ceilings can limit the pilot’s ability to maintain visual contact with the ground, increasing the risk of controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). Safe cloud clearance depends on the type of airspace and the altitude of the flight. FAA regulations specify minimum cloud clearance requirements for VFR flight:

- Class B Airspace: Clear of clouds.

- Class C and D Airspace: 500 feet below, 1,000 feet above, and 2,000 feet horizontally.

- Class E and G Airspace: Varies based on altitude.

3.3. Wind: Understanding Surface Winds and Crosswinds

Wind can significantly affect aircraft performance, especially during takeoff and landing. Strong surface winds can make it difficult to control the aircraft, while crosswinds can cause the aircraft to drift off course. Crosswind is the component of wind blowing perpendicular to the runway. Pilots must consider the maximum demonstrated crosswind component for their aircraft, which is the maximum crosswind in which a safe landing can typically be assured.

3.4. Icing: Recognizing and Avoiding Icing Conditions

Icing occurs when supercooled water droplets freeze on contact with the aircraft’s surfaces. Ice accumulation can increase weight, reduce lift, and impair control surfaces, leading to a dangerous flight condition. Icing conditions are most likely to occur in visible moisture (clouds, rain, snow) at temperatures between 0°C and -20°C. Pilots should avoid flying in known icing conditions or ensure their aircraft is equipped with de-icing or anti-icing equipment.

3.5. Turbulence: Assessing and Managing Air Turbulence

Turbulence is irregular motion of the atmosphere, causing the aircraft to experience sudden and erratic changes in altitude and attitude. Turbulence can range from light to severe and can be caused by various factors, including:

- Thermal Turbulence: Caused by rising currents of warm air.

- Mechanical Turbulence: Caused by wind flowing over obstacles, such as mountains or buildings.

- Wake Turbulence: Caused by the wingtip vortices of larger aircraft.

Pilots should assess the potential for turbulence by reviewing weather forecasts, PIREPs, and turbulence charts. If turbulence is encountered, pilots should reduce airspeed, maintain a level flight attitude, and brace for possible abrupt changes in altitude.

4. Decoding Weather Reports: METARs, TAFs, and NOTAMs

Decoding weather reports is a fundamental skill for pilots. METARs, TAFs, and NOTAMs provide essential information about current and forecast weather conditions and operational restrictions. Pilots need to understand these reports to make informed decisions about their flights.

4.1. Interpreting METARs: A Detailed Guide

METARs are hourly reports of current weather conditions at airports. They provide valuable information about wind, visibility, cloud cover, temperature, and other factors that can affect flight safety. Here’s a detailed guide to interpreting METARs:

- Station Identifier: A four-letter code identifying the airport (e.g., KEMT for El Monte Airport).

- Date and Time: The date and time the METAR was observed, in Zulu time (UTC).

- Wind: Wind direction and speed, in degrees and knots (e.g., 02005KT for wind from 020 degrees at 5 knots).

- Visibility: The horizontal visibility, in statute miles (e.g., 13SM for 13 statute miles).

- Weather Phenomena: Precipitation, obscurations, and other weather conditions (e.g., DZ for drizzle).

- Cloud Cover: The amount and height of clouds above ground level (AGL) (e.g., BKN060 for broken clouds at 6,000 feet AGL).

- Temperature and Dew Point: The air temperature and dew point, in degrees Celsius.

- Altimeter Setting: The barometric pressure used to set the altimeter, in inches of mercury (e.g., A2994 for 29.94 inches of mercury).

4.2. Analyzing TAFs: Forecasting Future Conditions

TAFs are forecasts of weather conditions expected at an airport during a specified period. They provide valuable information for flight planning, allowing pilots to anticipate potential weather hazards. Here’s how to analyze TAFs:

- Issuance Time: The date and time the TAF was issued, in Zulu time (UTC).

- Valid Period: The period for which the forecast is valid (e.g., 0718/0818 for valid from 1800 Zulu time on the 7th to 1800 Zulu time on the 8th).

- Wind: Forecast wind direction and speed, in degrees and knots.

- Visibility: Forecast horizontal visibility, in statute miles.

- Weather Phenomena: Forecast precipitation, obscurations, and other weather conditions.

- Cloud Cover: Forecast amount and height of clouds above ground level (AGL).

- Probability: The probability of specific weather conditions occurring (e.g., PROB30 for a 30% probability).

- Temporary Changes (TEMPO): Temporary fluctuations in weather conditions.

- From (FM): Rapid changes in weather conditions.

4.3. Understanding NOTAMs: Temporary Flight Restrictions

NOTAMs (Notices to Airmen) provide information about temporary flight restrictions (TFRs), airport closures, and other important operational information. Pilots must review NOTAMs before each flight to ensure they are aware of any restrictions or hazards along their route. NOTAMs are classified into several types:

- NOTAM (D): Information about airport facilities, services, and procedures.

- NOTAM (L): Information about taxiway closures, personnel and equipment near or crossing runways, and airport lighting aids that do not affect instrument approach criteria.

- FDC NOTAM: Information about amendments to instrument approach procedures and other regulatory changes.

- SAA NOTAM: Special Activity Airspace NOTAM.

- Example:

!FDC 1/1234 ZLA NAV VOR RADIAL 123 OUT OF SERVICE!FDC 1/1234: NOTAM number.ZLA: Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center.NAV VOR RADIAL 123: Navigation VOR radial 123.OUT OF SERVICE: Out of service.

- Example:

4.4. PIREPs: Enhancing Weather Awareness in Real-Time

PIREPs (Pilot Reports) are invaluable tools for enhancing weather awareness in real-time. These reports from fellow pilots provide firsthand accounts of actual weather conditions encountered during flight. PIREPs can confirm or contradict official forecasts, offering a more accurate picture of the current weather situation. By reviewing PIREPs, pilots can gain a better understanding of:

- Turbulence: Intensity and location of turbulence.

- Icing: Presence and severity of icing conditions.

- Cloud Tops: Height of cloud tops, useful for determining climb or descent profiles.

- Visibility: Actual visibility conditions encountered during flight.

- Wind Shear: Sudden changes in wind speed and direction.

PIREPs are especially valuable in mountainous terrain or areas with rapidly changing weather patterns.

5. Decision-Making Process: Go/No-Go Scenarios

The decision to fly or not fly is a critical one that should be based on a careful assessment of all available weather information. Pilots must develop a systematic approach to decision-making, considering their own experience, the capabilities of the aircraft, and the prevailing weather conditions.

5.1. Factors Influencing the Go/No-Go Decision

Several factors should influence the go/no-go decision, including:

- Pilot Experience: Less experienced pilots should be more conservative in their decision-making, avoiding marginal weather conditions.

- Aircraft Capabilities: The aircraft’s performance characteristics and equipment should be considered. Some aircraft are better equipped to handle adverse weather conditions than others.

- Weather Conditions: The current and forecast weather conditions should be carefully evaluated, paying close attention to visibility, ceiling, wind, icing, and turbulence.

- Regulations: Compliance with FAA regulations is mandatory. Pilots must ensure that they meet all minimum weather requirements for the intended flight.

- Personal Minimums: Pilots should establish personal minimums for weather conditions, based on their own experience and comfort level. These minimums should be more conservative than the regulatory minimums.

5.2. Using a Decision-Making Matrix

A decision-making matrix can help pilots systematically evaluate the various factors influencing the go/no-go decision. The matrix should include columns for each factor (e.g., visibility, ceiling, wind) and rows for different levels of severity (e.g., good, marginal, poor). Pilots can assign a numerical value to each level of severity and then calculate a total score. A predetermined threshold can then be used to determine whether to proceed with the flight.

| Weather Factor | Good (3) | Marginal (2) | Poor (1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visibility | > 5 SM | 3-5 SM | < 3 SM |

| Ceiling | > 3000 FT | 1000-3000 FT | < 1000 FT |

| Wind | < 10 KT | 10-20 KT | > 20 KT |

In this example, a total score of 7 or higher might indicate that the flight can proceed, while a score of 6 or lower might indicate that the flight should be delayed or canceled.

5.3. Case Studies: Analyzing Real-World Weather Scenarios

Analyzing real-world weather scenarios can help pilots develop their decision-making skills. By reviewing accident reports and case studies, pilots can learn from the mistakes of others and improve their ability to assess weather risks.

- Scenario 1: A pilot plans a VFR flight on a day with marginal visibility due to haze. The pilot checks the METAR and TAF, which indicate visibility of 4 statute miles and a ceiling of 2,500 feet. The pilot decides to proceed with the flight, but encounters deteriorating visibility en route. The pilot becomes disoriented and crashes into terrain.

- Analysis: The pilot should have been more conservative in their decision-making, given the marginal weather conditions. The pilot should have established personal minimums for visibility and ceiling and should have been prepared to turn back if weather conditions deteriorated.

- Scenario 2: A pilot plans an IFR flight on a day with forecast icing conditions. The pilot checks the weather briefing and determines that the aircraft is equipped with de-icing equipment. The pilot proceeds with the flight, but encounters severe icing en route. The pilot loses control of the aircraft and crashes.

- Analysis: The pilot should have been more cautious about flying in known icing conditions, even with de-icing equipment. The pilot should have been prepared to divert to an alternate airport if icing conditions became too severe.

5.4. The Importance of “Get-There-Itis” and Risk Mitigation

“Get-there-itis” is a dangerous mindset that can lead pilots to make poor decisions in the face of adverse weather conditions. Pilots must resist the temptation to press on with a flight, even if it means delaying or canceling the trip. Risk mitigation involves taking steps to reduce the likelihood of an accident. This can include:

- Obtaining a thorough weather briefing before each flight.

- Establishing personal minimums for weather conditions.

- Being prepared to turn back or divert to an alternate airport if weather conditions deteriorate.

- Ensuring that the aircraft is properly maintained and equipped for the intended flight.

- Maintaining proficiency in instrument flying skills.

6. Advanced Weather Tools and Techniques

Beyond basic weather reports, advanced tools and techniques can provide pilots with a more detailed understanding of weather conditions. These tools can help pilots make more informed decisions and improve flight safety.

6.1. Weather Radar: Interpreting Radar Images

Weather radar provides real-time information about precipitation, including its intensity and location. Pilots can use radar images to avoid thunderstorms, heavy rain, and other hazardous weather conditions. When interpreting radar images, pilots should pay attention to:

- Color Coding: Radar images use color coding to indicate the intensity of precipitation. Green indicates light precipitation, yellow indicates moderate precipitation, and red indicates heavy precipitation.

- Echo Tops: Echo tops indicate the height of the highest precipitation in a thunderstorm. Higher echo tops indicate more severe thunderstorms.

- Hook Echoes: Hook echoes are a characteristic feature of severe thunderstorms and can indicate the presence of a tornado.

- Hail Signatures: Hail signatures are radar patterns that indicate the presence of hail.

6.2. Satellite Imagery: Monitoring Cloud Cover and Development

Satellite imagery provides a broad view of cloud cover and development, allowing pilots to monitor weather systems over a large area. Satellite images are available in several formats, including:

- Visible Images: Show clouds and surface features as they appear to the human eye.

- Infrared Images: Show the temperature of clouds and surface features. Colder temperatures indicate higher clouds and more intense weather systems.

- Water Vapor Images: Show the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere. These images can help pilots identify areas of potential instability.

6.3. Skew-T Diagrams: Analyzing Atmospheric Stability

Skew-T diagrams are thermodynamic charts that show the vertical distribution of temperature, dew point, and wind in the atmosphere. These diagrams can be used to analyze atmospheric stability and identify potential for thunderstorms, icing, and turbulence. When analyzing Skew-T diagrams, pilots should pay attention to:

- Temperature and Dew Point: The difference between the temperature and dew point indicates the amount of moisture in the air. Smaller differences indicate higher humidity and greater potential for cloud formation.

- Lapse Rate: The rate at which temperature decreases with altitude. A steep lapse rate indicates an unstable atmosphere.

- Convective Available Potential Energy (CAPE): A measure of the amount of energy available for convection. Higher CAPE values indicate a greater potential for thunderstorms.

- Wind Shear: Changes in wind speed and direction with altitude. Wind shear can cause turbulence and can be a hazard during takeoff and landing.

6.4. Using Weather Models for Flight Planning

Weather models are computer simulations of the atmosphere that provide forecasts of weather conditions for several days into the future. Pilots can use weather models to plan flights and anticipate potential weather hazards. Popular weather models include:

- Global Forecast System (GFS): A global weather model run by the National Weather Service.

- North American Mesoscale (NAM) Model: A regional weather model run by the National Weather Service.

- High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) Model: A high-resolution weather model run by the National Weather Service.

When using weather models, pilots should be aware of their limitations. Weather models are not perfect and can sometimes produce inaccurate forecasts. Pilots should always verify the model forecasts with other sources of weather information, such as METARs, TAFs, and PIREPs.

7. Special Weather Hazards and How to Handle Them

Certain weather hazards pose unique risks to aviation and require special attention from pilots. These hazards include thunderstorms, icing, fog, and wind shear.

7.1. Thunderstorms: Avoiding Lightning and Severe Weather

Thunderstorms are one of the most dangerous weather hazards for aviation. They can produce lightning, hail, strong winds, and tornadoes. Pilots should avoid flying near thunderstorms whenever possible. If a thunderstorm cannot be avoided, pilots should:

- Maintain a safe distance: At least 20 nautical miles from severe thunderstorms.

- Fly around the storm: If possible, fly around the storm on the upwind side.

- Avoid flying under the storm: Avoid flying under the storm due to the risk of downbursts and wind shear.

- Monitor radar: Use weather radar to monitor the storm’s movement and intensity.

- Be prepared to divert: If necessary, divert to an alternate airport.

7.2. Icing: Strategies for Dealing with In-Flight Icing

Icing can significantly degrade aircraft performance and can lead to loss of control. Pilots should avoid flying in known icing conditions. If icing is encountered in flight, pilots should:

- Activate de-icing equipment: If the aircraft is equipped with de-icing or anti-icing equipment, activate it immediately.

- Change altitude: Climb or descend to an altitude where icing conditions are less severe.

- Increase airspeed: Increase airspeed to maintain lift and control.

- Avoid abrupt maneuvers: Avoid abrupt maneuvers, which can cause the aircraft to stall.

- Divert to an alternate airport: If necessary, divert to an alternate airport where icing conditions are not present.

7.3. Fog: Navigating Low-Visibility Conditions

Fog can significantly reduce visibility and make navigation difficult. Pilots should avoid flying in fog whenever possible. If fog is encountered in flight, pilots should:

- Use instruments: Rely on instruments for navigation.

- Maintain situational awareness: Be aware of the aircraft’s position and altitude.

- Reduce airspeed: Reduce airspeed to allow more time to react to potential hazards.

- Use landing lights: Use landing lights to improve visibility.

- Divert to an alternate airport: If necessary, divert to an alternate airport where visibility is better.

7.4. Wind Shear: Recognizing and Recovering from Wind Shear

Wind shear is a sudden change in wind speed and direction. It can occur near thunderstorms, frontal systems, and temperature inversions. Wind shear can be especially hazardous during takeoff and landing. If wind shear is encountered, pilots should:

- Recognize the signs: Be aware of the signs of wind shear, such as sudden changes in airspeed, altitude, and heading.

- Apply appropriate control inputs: Use appropriate control inputs to maintain airspeed and control.

- Go around: If wind shear is encountered during landing, perform a go-around.

- Increase airspeed: Increase airspeed during takeoff and landing to provide a margin of safety.

8. Resources for Ongoing Weather Education

Staying informed about weather is an ongoing process for pilots. Various resources are available to help pilots continue their weather education and improve their decision-making skills.

8.1. FAA Safety Briefings and Seminars

The FAA offers safety briefings and seminars on a variety of aviation topics, including weather. These briefings and seminars provide valuable information and insights into weather-related accidents and incidents.

8.2. Aviation Weather Courses and Training Programs

Several aviation weather courses and training programs are available to pilots. These courses provide in-depth instruction on weather theory, analysis, and forecasting.

8.3. Online Weather Forums and Communities

Online weather forums and communities can provide pilots with a valuable source of information and support. These forums allow pilots to share their experiences, ask questions, and learn from others.

8.4. Staying Current with Aviation Weather Publications

Several aviation weather publications are available to help pilots stay current with the latest weather information and techniques. These publications include:

- Aviation Weather Services (AC 00-45H): A comprehensive guide to aviation weather services.

- Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA-H-8083-25B): Provides information on weather theory and aviation weather services.

9. Practical Tips for Daily Weather Assessment

Assessing weather conditions should be a daily habit for pilots. The information should be carefully gathered and analyzed to ensure the safety of each flight.

9.1. Establishing a Consistent Weather Check Routine

Establishing a consistent weather check routine can help pilots ensure that they do not overlook any important information. This routine should include:

- Reviewing METARs and TAFs for the departure and destination airports.

- Checking for NOTAMs along the route.

- Monitoring weather radar and satellite imagery.

- Analyzing Skew-T diagrams.

- Reviewing weather models.

- Obtaining a weather briefing from Flight Service.

9.2. Using Checklists to Ensure Thoroughness

Using checklists can help pilots ensure that they are thorough in their weather assessment. A weather checklist should include:

- Date and time of weather check.

- Source of weather information.

- Weather conditions at departure and destination airports.

- Forecast weather conditions along the route.

- Potential weather hazards.

- Decision to fly or not fly.

9.3. Documenting Weather Information and Decisions

Documenting weather information and decisions can provide a valuable record of the pilot’s thought process. This record can be used to analyze past flights and improve future decision-making.

9.4. Cross-Checking Information from Multiple Sources

Cross-checking information from multiple sources can help pilots ensure that they are getting an accurate picture of weather conditions. This can include:

- Comparing METARs and TAFs from different sources.

- Verifying weather model forecasts with radar and satellite imagery.

- Obtaining a weather briefing from Flight Service and comparing it to other sources of information.

10. Flyermedia.net: Your Aviation Weather Resource

At flyermedia.net, we are committed to providing pilots with the most up-to-date and accurate weather information available. Our website offers a variety of resources to help pilots make informed decisions about their flights, including:

- Real-time weather data: Access to METARs, TAFs, radar images, and satellite imagery.

- Weather analysis tools: Tools for analyzing Skew-T diagrams and weather models.

- Aviation weather articles: Articles on weather theory, analysis, and forecasting.

- Weather forums: A forum for pilots to share their experiences and ask questions.

Visit flyermedia.net today to access these valuable resources and improve your aviation weather knowledge.

10.1. Accessing Training and Career Opportunities via flyermedia.net

For those looking to advance their careers in aviation or get started in flight training, flyermedia.net offers a wealth of resources. You can find:

- Listings of flight schools and training programs across the United States, including those in aviation hubs like Daytona Beach.

- Information on aviation career paths, from pilots and air traffic controllers to aircraft mechanics and aviation managers.

- Articles and guides on pilot certification, including FAA requirements and how to prepare for exams.

Whether you’re just beginning to explore the world of aviation or seeking to take your career to new heights, flyermedia.net is your go-to resource.

Address: 600 S Clyde Morris Blvd, Daytona Beach, FL 32114, United States

Phone: +1 (386) 226-6000

Website: flyermedia.net

Are you ready to take your love of aviation to the next level? Visit flyermedia.net today to explore flight training programs, access the latest aviation news, and discover the myriad career opportunities that await you in the skies. Your journey to the skies starts here!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can I fly today if the METAR reports light rain?

Yes, you can fly if the METAR reports light rain, but it depends on your experience level and the aircraft’s capabilities. Check visibility, cloud cover, and wind conditions to ensure they meet VFR or IFR minimums.

2. What does “BKN030” mean in a METAR?

“BKN030” means broken clouds at 3,000 feet above ground level (AGL).

3. How do I find NOTAMs for my flight route?

You can find NOTAMs on the FAA website or through aviation apps like ForeFlight and Garmin Pilot.

4. What should I do if I encounter turbulence in flight?

Reduce airspeed, maintain a level flight attitude, and brace for possible abrupt changes in altitude.

5. Is it safe to fly near thunderstorms?

No, it is not safe to fly near thunderstorms due to lightning, hail, strong winds, and tornadoes. Maintain a safe distance of at least 20 nautical miles from severe thunderstorms.

6. How does icing affect aircraft performance?

Icing can increase weight, reduce lift, and impair control surfaces, leading to a dangerous flight condition.

7. What is wind shear, and why is it dangerous?

Wind shear is a sudden change in wind speed and direction. It can cause sudden changes in airspeed, altitude, and heading, which can be dangerous during takeoff and landing.

8. How can I stay current with aviation weather information?

Attend FAA safety briefings, take aviation weather courses, participate in online weather forums, and read aviation weather publications.

9. What are personal minimums, and why are they important?

Personal minimums are self-imposed limits for weather conditions, based on your experience and comfort level. They are important because they ensure that you do not fly in conditions that are beyond your capabilities.

10. Where can I find flight schools and training programs?

You can find listings of flight schools and training programs on flyermedia.net and other aviation websites.