Ever looked up and wondered about the speed of that aircraft overhead? It might seem to be drifting slowly, but in reality, airplanes are incredibly fast, especially jet planes that can travel close to the speed of sound. The high altitude makes it difficult to truly grasp their velocity.

This article will explore the fascinating world of airplane speeds, detailing how fast different types of aircraft fly today and what the future holds for air travel velocity.

Key Insights into Airplane Speed

- Airspeed is the standard measurement for aircraft speed, not ground speed.

- The Mach scale becomes crucial when discussing speeds approaching the speed of sound.

- Commercial airliners fly at high subsonic speeds, close to Mach 1, for optimal fuel efficiency and performance.

- Military jets are designed for supersonic flight, offering tactical advantages.

- General Aviation aircraft operate at lower, subsonic speeds.

- Supersonic passenger flight may be on the verge of a comeback, with hypersonic travel potentially following in the future.

Commercial Airliner Speeds: Balancing Time and Fuel

For commercial airlines, flight speed is a critical factor balanced against fuel consumption and travel time. Flying faster reduces travel time but significantly increases fuel burn. Aircraft manufacturers carefully determine the ideal cruise speed for airliners based on their intended routes and operational efficiency.

Consider the Airbus A320 and Boeing 737, two of the most common narrow-body airliners. They typically cruise at around Mach 0.78, which translates to approximately 587 miles per hour (945 kilometers per hour).

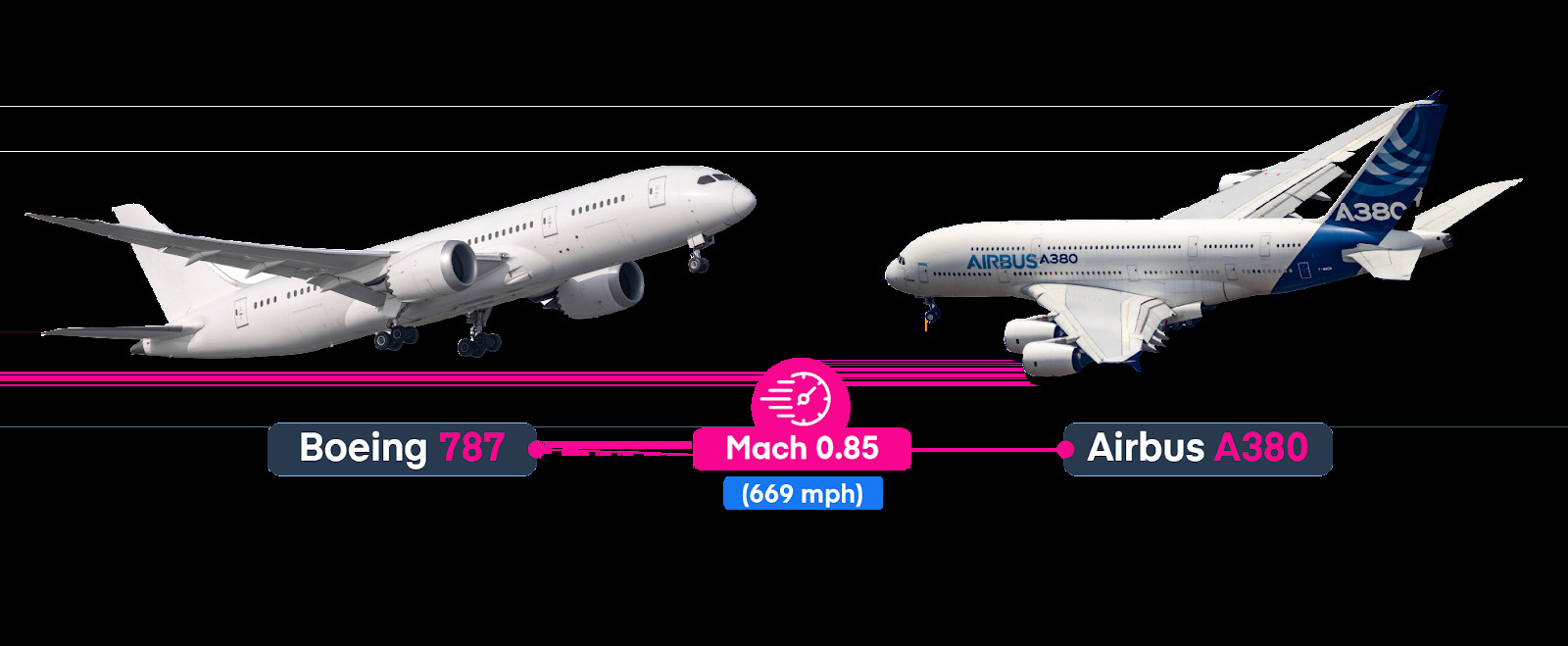

Larger, long-haul airliners like the Boeing 787 Dreamliner and the Airbus A380 are designed for extended routes and therefore often fly slightly faster to save considerable time on long journeys. These aircraft usually cruise at Mach 0.85, or about 669 mph (1076 km/h). The time savings on transcontinental flights are much more significant for these faster speeds.

Boeing 787 and Airbus A380.

Boeing 787 and Airbus A380.

Alt text: Side-by-side comparison of a Boeing 787 Dreamliner and an Airbus A380, highlighting their size difference in commercial aviation.

Private jets prioritize speed even further. Operators of private aircraft are often willing to spend more on fuel to minimize travel time for passengers. Modern private jets often fly at higher altitudes than commercial airliners, ranging from 45,000 to 51,000 feet. The thinner air at these altitudes reduces drag, enabling aircraft such as the Gulfstream G650 and Bombardier Global 7500 to achieve cruise speeds of Mach 0.90 (around 715 mph or 1150 km/h).

The Concorde remains the fastest commercial airplane ever to operate. Introduced in 1976, this marvel of engineering was specifically designed for supersonic flight. It could cruise at Mach 2.04 (1,559 mph or 2,509 km/h), cutting transatlantic journeys to under three hours – a trip that takes conventional jets at least six hours.

A picture of the Concorde.

A picture of the Concorde.

Alt text: Iconic side profile of the Concorde supersonic airliner in flight, showcasing its delta wing design and speed capability.

However, the Concorde’s incredible speed came at a high price. Its operational costs were significantly higher than subsonic aircraft, ultimately leading to its retirement in 2003.

Military Jet Speeds: Speed as a Tactical Advantage

Military jets have a diverse range of speed capabilities based on their specific missions.

Military transport, tanker, and cargo aircraft share similar operational requirements with commercial airliners, and their speeds reflect this similarity.

For instance, cargo aircraft like the Boeing C-17 Globemaster and the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy typically cruise at around Mach 0.77 (approximately 520 mph or 837 km/h). These are slightly slower than commercial jets because their design prioritizes cargo capacity and the ability to operate from shorter airfields over sheer speed.

Fighter jets, on the other hand, are built for speed. In aerial combat, speed provides a critical tactical and strategic advantage. Consequently, all modern fighter jets are capable of supersonic flight.

Multi-role fighters like the F-35 Lightning II and F/A-18E Super Hornet can reach speeds of Mach 1.6 (1,190 mph or 1,915 km/h). Interceptor aircraft, such as the F-16 Fighting Falcon, prioritize speed even more over stealth or carrier operability, achieving speeds up to Mach 2 (1,353 mph or 2,177 km/h).

F-35 and F-16.

F-35 and F-16.

Alt text: A formation flight of a Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II and a General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, representing multi-role and interceptor military jets.

It’s important to note that fighter jets often achieve their maximum speeds for short bursts using afterburners, which dramatically increase engine thrust. In typical cruise flight, they operate at subsonic speeds, around Mach 0.9 (621 mph or 1000 km/h).

Some advanced military jets possess “supercruise” capability, allowing them to sustain supersonic flight without using afterburners. Examples include the F-22 Raptor, which can supercruise at Mach 1.82 (1,220 mph or 1,963 km/h), and the Eurofighter Typhoon at Mach 1.5 (1,035 mph or 1,666 km/h). With afterburners, the F-22 Raptor can reach an even higher speed of Mach 2.25 (1,500 mph or 2,414 km/h).

The Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird holds the record as the fastest jet aircraft ever built. This high-altitude, long-range reconnaissance aircraft, used during the Cold War, could fly at an astonishing Mach 3.32 (2,193 mph or 3,529 km/h). This extreme speed allowed it to outrun any interceptor aircraft or surface-to-air missiles, operating unchallenged for over two decades until satellite reconnaissance technology became prevalent.

Small Airplane Speeds: Slower Pace for Shorter Distances

At the lower end of the speed spectrum are small general aviation aircraft. These airplanes typically fly below 300 knots (Mach 0.45) and at altitudes under 25,000 feet. At these lower speeds, the Mach scale is less relevant, and pilots usually use indicated airspeed (IAS).

General Aviation aircraft include popular four-seater models like the Cessna 172 Skyhawk, Piper Cherokee, and Diamond DA40. These aircraft typically cruise around 125 knots (143 mph or 230 km/h) with maximum speeds of about 160 knots (184 mph or 296 km/h). Newer single-engine aircraft like the Cirrus SR22 and Columbia 350 can reach speeds of up to 200 knots (230 mph or 370 km/h).

Diamond DA40.

Diamond DA40.

Alt text: Front three-quarter view of a Diamond DA40 light aircraft on the tarmac, representing modern general aviation.

These smaller aircraft are considerably slower than jets because they utilize piston engines, which produce significantly less power compared to jet engines. Piston engines also become less efficient at higher altitudes where the air is thinner.

To enhance performance at higher altitudes, especially above 15,000 feet, manufacturers often equip aircraft with turbochargers. Turbocharged variants of general aviation aircraft gain a noticeable boost in both top speed and achievable cruise altitudes.

For example, the Mooney M20 Bravo Turbo can fly approximately 35 knots (41 mph or 66 km/h) faster than its non-turbocharged counterpart. It also boasts a higher cruise altitude of 25,000 feet compared to the standard model’s 18,500 feet.

In modern general aviation, the emphasis has shifted towards improving comfort, safety features, and fuel efficiency rather than dramatically increasing speed. Speed is not typically the primary design driver for this class of aircraft.

The Future of Airplane Speed: Supersonic and Hypersonic Horizons

Given the challenges associated with transonic flight (approaching Mach 1), it’s unlikely that conventional commercial airliners will significantly exceed current speeds. To drastically reduce global travel times further, entirely new aircraft designs are required.

However, supersonic passenger flight is potentially on the cusp of a resurgence, with several projects currently under development aiming for first flights as early as 2024. NASA and Lockheed Martin’s X-59 QueSST and Boom Supersonic’s Overture are leading contenders in this renewed supersonic era.

Why did supersonic passenger travel fade away after the Concorde?

While high operating costs were a major factor in the Concorde’s demise, another significant issue was the intense sonic boom it generated when exceeding Mach 1.

A sonic boom is a loud, thunder-like noise created by shockwaves as an aircraft flies faster than the speed of sound. This disruptive noise led to substantial public opposition in populated areas overflown by the Concorde.

Consequently, aviation authorities like the FAA placed bans on civil supersonic flight over land. These restrictions severely limited the routes Concorde could operate and discouraged further development in the supersonic sector for many years.

NASA’s X-59 QueSST mission aims to address the sonic boom problem by significantly reducing it to a much quieter “sonic thump.” The X-59’s unique, elongated shape is designed to direct sonic booms upwards, minimizing the noise impact on the ground while cruising at Mach 1.4 (937 mph or 1,508 km/h). NASA hopes that successful testing, with first flight anticipated in 2024, will persuade regulators to reconsider the ban on supersonic flight over land.

Boom Supersonic’s Overture is an 80-passenger airliner designed to fly at Mach 1.7 (1,100 mph or 1,770 km/h). Currently under active development, the Overture is projected to enter service by 2026. Despite previous failed attempts at creating a Concorde successor, such as the Aerion AS2 and Boeing Sonic Cruiser, the Boom Overture appears promising, with confirmed orders from major airlines like United and American Airlines, totaling 130 aircraft in its order book, signaling a potentially bright future for supersonic commercial travel.

Beyond supersonic, the realm of hypersonic flight – speeds exceeding five times the speed of sound – represents the next frontier.

The North American X-15 holds the record for the highest speed achieved by a crewed, powered aircraft, reaching Mach 6.7 (4,520 mph or 7,274 km/h) in 1967. Much of the hypersonic development since then has focused on missiles and rockets.

However, in June 2023, Boeing unveiled a concept for a hypersonic passenger aircraft capable of crossing the Atlantic in just two hours. This concept envisions using a combination of jet and ramjet engines to achieve cruise speeds of Mach 5. While still in the conceptual phase, hypersonic passenger travel could become a reality within the next 20 to 30 years.

Conclusion

Still curious about the different ways we measure airplane speed? Dive deeper into the topic with our comprehensive guide to the six types of airspeed.